by Roselyn Fauth and Geoff Cloake 2025

Timaru_Alexandra_Lifeboat_Story Sheet_8 x A4.pdf

This is the story of our Alexandra lifeboat. Why it matters to us today.

Built in Britain in 1862 and brought to Timaru in 1863, the Alexandra lifeboat was ordered by the Canterbury Provincial Government at the time, from England, at a cost of £300, for the people of this town. At the time, Timaru’s coast was exposed and unforgiving. Ships anchored offshore in the open Roadstead, and when the sea rose suddenly, lives were often at risk. As the harbour works and modern port infrastructure reduced the need for open Roadstead rescues, Alexandra’s role shifted from working vessel to community taonga. She appeared in parades and commemorations, a physical reminder that progress was paid for in risk, loss, and volunteer grit. The vessel was put on display at the bay for its 50th anniversary and then relocated to the Timaru Landing Services building, and then into storage at the Timaru Botanic Gardens. In 2025 it returned to the bay thanks to the creation of its new home championed and fundraised for by the community.

Congratulations to the Timaru Suburban Lions. They have turned a long discussed dream into timber, steel, and shelter, raising the funds and momentum to bring Alexandra back to Caroline Bay in a purpose built structure where the public can see her, and where her story can be told properly.

Each time she has been relocated, it has marked a change in Timaru’s relationship with the sea: from survival, to prevention, to remembrance, to education. The Lions have added a new chapter, one that returns her to the Bay, close to the water she once faced, and close to the families who still feel that history in their bones.

From a community effort, one of our most powerful relics of our past now has a place to stand, look seaward, and remember.

Ships at sea could loose their anchor and drift into danger. This is a very old anchor at the Caroline Bay Playground.

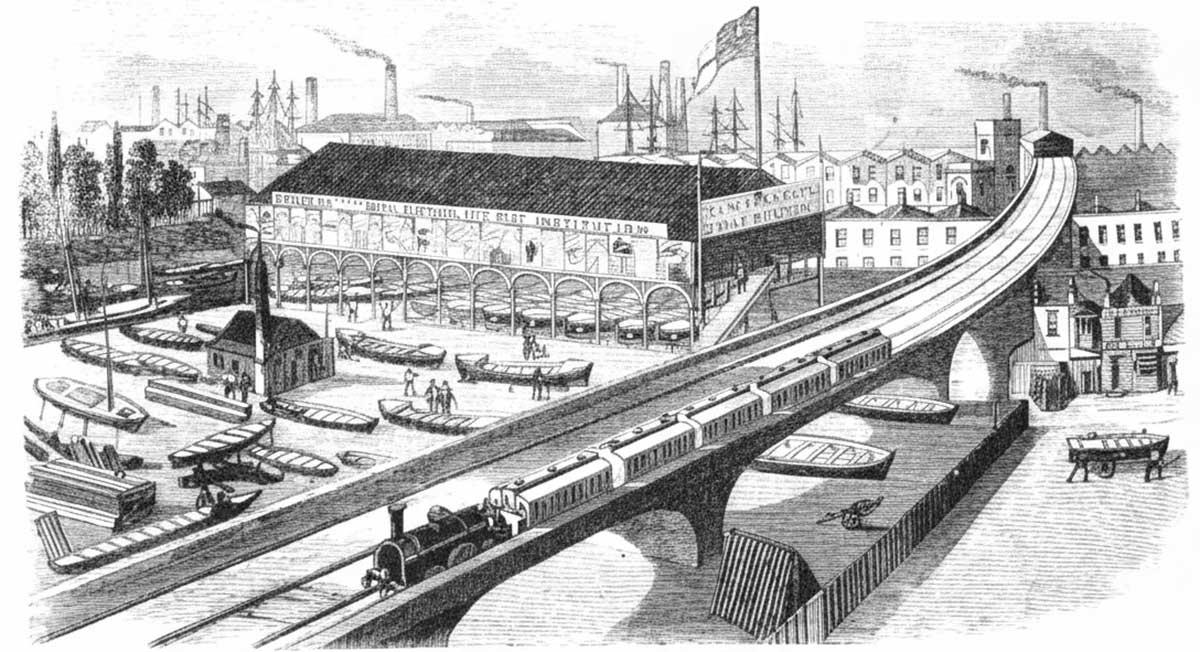

Shipyard where the Alexandra was built, Britain. Based on a image of Messrs Forrest of Limehouse life-boat building yard where Alexandra Timaru Lifeboat was built - The Illustrated London News Google Books - Page 478

Shipyard where the Alexandra was built, Britain. Based on a image of Messrs Forrest of Limehouse life-boat building yard where Alexandra Timaru Lifeboat was built - The Illustrated London News Google Books - Page 478

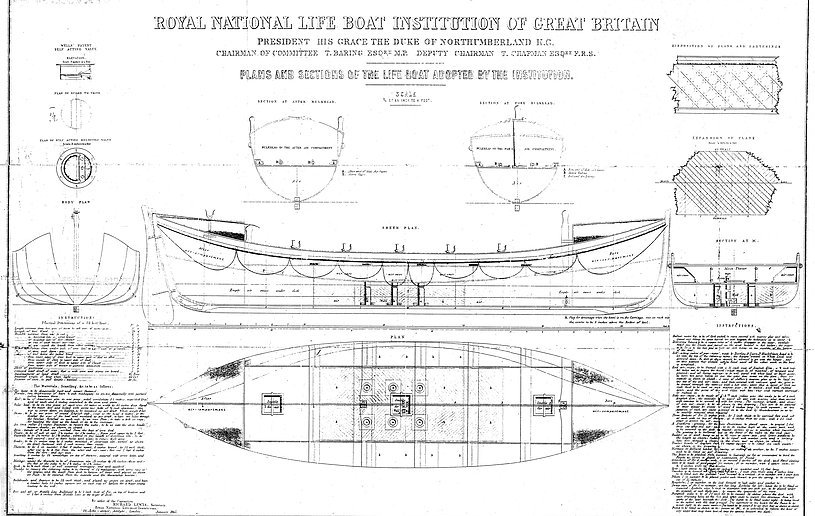

Royal National Life Boat Institution of Great Britain Plans

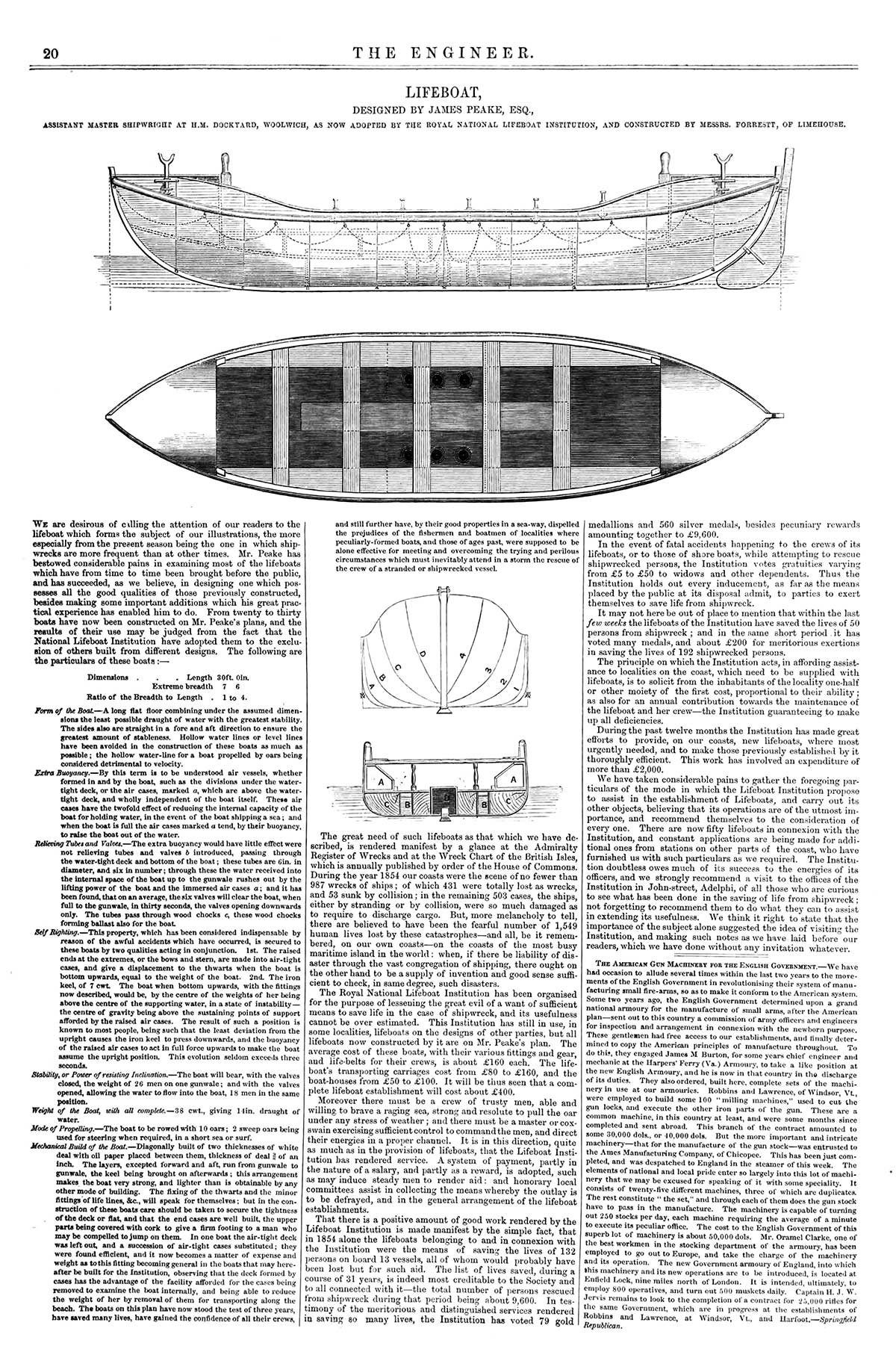

An Engineering article about the RNLI lifeboat design.

The Alexandra arrived at a moment of global change in sea rescue. In 1854, Queen Victoria granted a Royal Charter to the National Lifeboat Institution, later known as the RNLI, giving authority to a new, coordinated approach to saving lives at sea. Central to this was the development of self-righting lifeboats, designed to survive capsizing and heavy surf.

One of the strongest supporters of this work was Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts, a leading Victorian philanthropist who helped fund lifeboats, equipment, crews, and seafarers’ welfare. Through this combination of design, organisation, and philanthropy, lifesaving technology advanced rapidly and spread far beyond Britain.

Prince Albert Edward “Bertie” and Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Illustration based on the wedding announcement of the couple. Invitation, 1901, New Zealand, by Benoni William Lytton White, A.D. Willis Ltd. Purchased 2001. Te Papa (GH009568).

The band rotunda and town square in Timaru are named after Princess Alexandra. Based on a postcard entitled "Alexandra Square, Timaru", circa 1910. Features the band rotunda gifted by Charles Bowker in 1903 in the foreground, with the James Bruce & Co. (or Timaru Milling Co.) flour mill on High Street in the left background. Both the reserve and the life boat were named after British Royal. Laid out by Samuel Hewlings as Market Place Alexandra Square has been a horse paddock, a market reserve, a site for travelling circuses, a place to play hockey or cricket and a place that needed beatifying. In 1904 Timaru's first band rotunda was built at Alexandra Square and twelve garden seats, at a cost of £600, a gift to the people of the city, by Mr Charles Bowker, who lived in College Rd, in a two storied house named "The Pines." This was the first civic gift of the kind to the city. Later open air meetings and band concerts were held here.

Timaru was one of the earliest ports internationally to adopt this new generation of lifeboat, placing the town at the forefront of lifesaving practice at a time when many communities still relied on open surfboats. The lifeboat was christened Alexandra, in honour of Princess Alexandra of Denmark, who married Queen Victoria’s eldest son, Albert Edward, in 1863. Her name became associated with humanitarian values and modern progress. Timaru’s lifeboat and Alexandra Square were named in her honour, reflecting the town’s connection to Britain.

Before the harbour existed, Timaru lived by the sea and suffered because of it. Rescue depended on strength, skill, and judgement, often carried out by volunteers launching into heavy surf with little protection. While the Roadstead posed constant danger when swell or storms arrived, not every wreck was caused by weather alone. Some vessels were poorly maintained, damaged, or unfit for conditions. Others suffered shifted cargo, mechanical failure, or human error.

Belfield Woollcombe’s harbour flag instructions. The Landing Service at the foot of Strathallan Street, was known as Cains Landing. Surfboats were pulled up slipways into sheds and unloaded. Timaru owes its size and prosperity to its port.

In 1857, mariner Captain Henry Cain established a landing service at the foot of Strathallan Street, using surfboats to transfer passengers and goods between ships anchored offshore and the shore. It later came under government control and formed the backbone of Timaru’s early port operations.

Statue of Captain Henry Cain at the Timaru Landing Service Building on George Street. After 30 years as a mariner, Capt. Cain moved to Timaru in 1857 to run a landing service at the foot of Strathallan Street, for Henry Le Cren. He and his wife Jane lived in one of the first five European houses on the shore. Capt. Cain managed Timaru’s landing services and welcomed the Alexandra lifeboat in 1863. He served as mayor from 1870 to 1873 and died in 1886, allegedly poisoned by his son-in-law.

This statue commemorates Captain Cain, who established a landing service on Strathallan Street. It was purchased by the Government. When locals were dissatisfied with the Government Landing Service, in 1868 local merchants formed the Timaru Landing and Shipping Company. Cain bought this service on George Street in 1870. The Timaru Landing Service Building was constructed from local bluestone on George Street behind the landing service. It is the last remaining building of its type in the southern hemisphere. The completion of Timaru’s artificial port in the 1880s made the landing services obsolete. The building is now a tourist information centre, houses the Te Ana Rock Art Museum, restaurants and bars. The building was rescued and restored by the Timaru Civic Trust.

Usually towns were founded by either government or private enterprise. Timaru was established by both. In 1853 the Rhodes brothers surveyed a town behind Caroline Bay; three years later the government surveyed its own town south of the Rhodes’s settlement. North Street divided the towns. Eventually the two settlements merged. The Rhodes used the sheltered shore at Timaru, the site of an abandoned whaling station, to land stores and ship wool. A plaque on the Timaru Landing Services building marks the site of Timaru's first European house. It was built for the Rhodes in 1851 when they were establishing their Levels Station.

In 1855 the shepherd James ‘Jock’ Mackenzie was caught inland from Fairlie with 1,000 sheep from the Levels station. He protested his innocence, but was jailed. He escaped twice before being pardoned. His exploits, and those of his dog, won him widespread public sympathy and he became a folk hero. The area where he was apprehended was subsequently named ‘the Mackenzie Country’. This memorial to Mackenzie and his dog is in Fairlie.

Former whaler Samuel Williams and his wife and children lived in this house operating the initial sheep station landing. Sam had a good knowledge of the local coast as he had worked here earlier as a boat steerer in 1839 for the Sydney-based Weller brothers who established a short-lived whaling station at Timaru.

Weller Brothers whale pot at Caroline Bay

Boatmen from Deal arrived with the head of their team Strongwork Morrison who became Timaru's early beachmaster. Two of their crew, Morris Corry and Robert Bowbyes were the first recorded sea rescue deaths on the timaru coastline. They used to the rescue in a surfboat. They were the first to be buried at Timaru's cemetery. One in a marked grave with a headstone for he and his wife. The other is the first recorded unmarked grave.

In 1857 Belfield Woollcombe was in Timaru as the governments official representative was appointed as harbourmaster.

The population jumped from around 17 by 110 in Timaru, when the Strathallan Ship arrived in January 1859 with British settlers. They were joined by a further 360 immigrants in 1862–63. By 1866 the town had a population of 1,000, and it became a borough in 1868.

The population doubled in the 1870s, then stagnated. From 1896 until 1911 there was relatively high growth, linked to more intensive farming in the region. Timaru became a city in 1948.

Before roads and bridges, the sea was South Canterbury's highway to the rest of the country and the global markets. South Canterbury’s northern and southern boundaries were large, snow-fed braided rivers that were difficult for early travellers to cross. Ai illustration based on photo of a traffic bridge in Temuka 1912. By Muir and Moodie Te Papa O-001799. The bridging of South Canterbury’s wide, braided rivers made travel easier and faster. South Canterbury’s isolation was ended by construction of a main trunk railway between Christchurch and Dunedin. Completed in 1878, it linked Timaru to both cities, and to Temuka and Waitaki North (Glenavy) along the way. South Canterbury had only two significant branch lines. The line from Washdyke reached Pleasant Point in 1875 and was opened to Eversley, beyond Fairlie, in 1884. The ‘Fairlie Flyer’ passenger train became part of South Canterbury folklore. Better transport links in the 1860s and 1870s fostered the growth of the inland towns. Geraldine, Temuka and Waimate began life as sawmilling settlements, and Fairlie as a railway terminus.

The Fairlie Flyer train steaming down the rail. Illustration based on photograph by Geoff Cloake. Until the mid-1950s, road traffic between Christchurch and Dunedin shared the bridge across the Waitaki River at Glenavy with trains. When the bridge was closed to allow a train to cross, up to 200 cars might have to queue for half an hour or more. When a new road bridge was opened in 1956, the procession of sightseers stretched for 1.5 kilometres. In 1871, as mayoress, Jane Cain (married to Captain Cain) turned the first sod for the Timaru to Christchurch railway line.

From the cliffs above the Roadstead, lookouts provided a place to stand and watch for trouble. Flags were raised to warn ships, signal changing conditions, and summon assistance. Without radios or engines, judgment and timing mattered. A delay of minutes could cost lives.

Ai illustration based on William Ferrier (1855-1922), Breakwater Timaru Running a Southerly Gale, 1888, Oil on canvas - Aigantighe Art Gallery Collection 2002.10

Work began in 1878 with the construction of the 700-metre southern breakwater. In the late 1880s, the northern breakwater was built to keep sand shoals out of the harbour. Between 1899 and 1906 the eastern extension of the main breakwater was completed, preventing shingle drifting north into the harbour. During the 20th century the breakwaters were extended, realigned and raised. Before the harbour construction the Roadstead posed constant danger when swell or storms arrived. However not every wreck was caused by weather alone. Some vessels were poorly maintained, damaged, or unfit for the conditions. Others suffered shifted cargo, mechanical failure, or human error. The risks of ship-to-shore transfer in an exposed anchorage were ever-present, even on calm days.

The death of James Melville Balfour, New Zealand’s Colonial Marine Engineer, revealed the deeper urgency behind Timaru’s harbour development. Balfour was responsible for advising on coastal works and improving the efficiency and safety of ports throughout the colony. He had been in Timaru examining the coastline and harbour conditions, including the behaviour of drifting shingle, as part of this work.

Timaru Experimental Groin and James Balfour Grave in Dunedin. Left: South Canterbury Museum 0560-2.

In 1869, while attempting to board a steamer anchored offshore, Balfour was drowned when the surfboat carrying him capsized. He was 38 years old, travelling in the ordinary course of his duties and bound for Oamaru to attend matters connected with another maritime death. There was no storm that day. The man charged with improving harbour safety lost his life in the very waters he was assessing. His death reinforced a stark truth: rescue alone was not enough. Timaru needed lasting protection.

The Alexandra was housed in a shed at the foot of Strathallan Street, beside the landing service first run by Captain Henry Cain and later by the Government. From here, passengers and cargo were transferred through heavy surf, day after day. The lifeboat formed part of a wider rescue system that included harbour lookouts, flag signalling, the Rocket Brigade, and shore-based crews. As the service developed, crews became trained and, for a time, paid professionals.

The risks were constant. In 1869, lifeboatman Cameron Duncan drowned while attempting to reach the vessel Twilight during a rescue involving the Alexandra. Government and community subscriptions were raised to support his family and burial. Duncan was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in Row 0 at Timaru Cemetery, a reminder that not all who gave their lives were publicly commemorated at the time.

This area at the Timaru cemetery is known as area F, and somewhere here lies Cameron Duncan in a grave paid for by community fundraising and the government. The grave is unmarked and its specific location is unknown. Cameron is listed in Row 0 in the online Timaru District Council Cemetery database.

When crew allowances were reduced and equipment wore out, local women stepped forward, organising concerts, subscription lists, and sewing work to support rescue services, replace gear, and assist families affected by loss. In 1873, supporters formed the Alexandra Lifeboat Lodge, reinforcing the belief that lifesaving was a shared civic responsibility.

The harbour board established quarries to shift volcanic rock known as basalt or Timaru blue stone to help develop the Port of Timaru, erosion control, block for civic work including drains and bridges and the heritage buildings, the the Timaru Landing Services building that was rescued and restored by the Timaru Civic Trust, which housed the lifeboat for many years.

Around 2–2.5 million years ago, lava erupted from a source near Waipouri/Mt Horrible and flowed like fingers down to what is now the coast of Timaru. The lava formed the reefs that later provided shelter for vessels. The reefs provided habitat for marine life which became a important food source for Maori. Centennial Park is one of the quarries that was owned by the Timaru Harbour Board to accumulate material for the Port of Timaru's construction and ongoing development.

Cart that is on display at Pleasant Point Railway Museum - the cart was used to move basalt rock from the harbour board quarry to construct the harbour

Black Sunday, 14 May 1882: The Benvenue and City of Perth wrecks. By J. Dickie. Brodie Collection, La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria. 9917507453607636

The Alexandra’s darkest and finest hours came on Black Sunday, when the ships Benvenue and City of Perth were wrecked in a sudden and violent sea. Volunteers launched the lifeboat again and again, refusing to stop while men remained in peril. Some did not come home. The scale of courage shown that day was formally recognised. Medals were awarded to those involved in the rescue efforts, and a public memorial was later erected in Timaru to honour both the dead and the living.

News of the disaster spread across the globe

The above scan is of the Illustrated Australian News. It reports the Benvenue Shipwreck and includes three illustrations. (1882, June 10). Illustrated Australian News (Melbourne, Vic. : 1876 - 1889), p. 85. Retrieved December 10, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page5731583

From the 1860s-1880s, Timaru had a bad reputation among shipowners because of the great number of wrecks which occurred in the roadstead. Timaru was not really worse than some other New Zealand open ports, but the people here heard more of the higher insurance of vessels coming here than the high rates for other places. The losses wore probably in most cases due to the vessels anchoring too close to the beach in order to reduce the work of lightering. The reports of early visitors declared the holding ground to he exceedingly good. Of 28 losses, seven were stranding's, and out of the first 23, totaling under 3500 tons, only one was over 500 tons. Two of the later wrecks were the “City of Perth” and the “Benvenue,” but the former was eventually refloated. Just as the early progress of the town received severe set-backs as a result of disastrous fires, so the prestige of the port- was seriously imperiled by this succession of wrecks. The most memorable and the most spectacular of them was the stranding of the “City of Perth” and the loss of the “Benvenue,” on the afternoon of Sunday, May 14, 1882.

Telegraph shared messages over distances with dots and dashes. This helped to spread news quickly.

The Benvenue ship’s bell and the Bravery Award medals that are displayed at the South Canterbury Museum.

Among those most closely associated with Timaru’s rescue services was Captain Alexander Mills, who served as Harbour Master and led the Timaru Volunteer Rocket Brigade. He witnessed many of the town’s shipwrecks and carried the responsibility of balancing safety with the practical demands of a working port. On Black Sunday, 14 May 1882, Captain Mills took part in the rescue attempts during the wreck of the Benvenue and the City of Perth. He made it back to shore, but later that day died from shock and exposure, as ruled by the inquest. He was 48 years old.

The men recognised by the St John’s Masonic Lodge for their bravery in the Black Sunday rescue. Forty received medals in person in August 1882: W. Collis, J. McIntosh, A. H. Turnbull, J. Cracknell, J. Thompson, G. Sunnaway, R. Collins, John Reid, J. Houlihan, M. Lekoy, J. A. Petterson, G. Findlay, C. Gruhm, J. Henneker, W. Halford, G. Shirtcliffe, W. Walls, R. H. Balsom, T. Hart, G. Davis, W. S. Smith, F. McKenzie, T. Morgan, C. Vogeler, P. Bradley, D. Bradley, S. J. Passmore, J. Crocombe, C. Moore, A. Schabb, T. Martin, M. Thompson, W. Oxby, I. J. Bradley, H. Trouselot, W. H. Walls, J. Isherwood, A. L. Haylock, John Ivey, and W. Budd. Three were absent and their medals were sent to Scotland: G. Mentac, C. McDonald, and W. R. McAteer.

The medal was designed by Arthur L. Haylock for The Masonic Lodge of St John, to present to the 43 involved in the rescue attempts of 14 May 1882. He joined the Government Service and moved to Timaru, where he joined the Timaru Rocket Brigade. He recorded first-hand recollections (c. 1877–1882) and later compiled records of shipwrecks and rescues.

The Harbourmaster, Captain Alexander Mills and his grave at Timaru Cemetery. His wife Margaret and several of their children rest here as well. Mills was widely respected in Timaru and New Zealand. Many visited his house to pay their respects after his death. The community expressed heartfelt sympathy for his family. A letter of condolence from the Lodge of St. John, Timaru, emphasized his virtues and loss. Hon. Mr. Rolleston expressed grief and acknowledged Mills' dedication and duty. Funeral arrangements included a public closure of businesses from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m. The Rocket Brigade, Masonic Lodges, C Battery of Artillery, and Timaru Volunteer Fire Brigade planned to attend the funeral in full uniform.

Living overlooking the harbour, Margaret may have seen Capt. Alexander Mills fly flags to instruct ships, keep a lookout, and summon rescues. Did they talk about his frustrations? Did he feel caught between the harbour board’s, expectations, who wanted ships close to shore for efficiency, yet he knew that keeping ships far enough out sea reduced the risks of danger in rough seas?

Capt. Mills was fired after the City of Cashmere wrecked and was reinstated before Black Sunday. He must have felt immense pressure to rescue the City of Perth, and relief to have the Alexandra lifeboat available. He died from exposure at age 48 after attempting to salvage the City of Perth.

While grieving, Margaret faced public scrutiny. An enquiry recommended restoring and training a lifeboat crew, which was ironic, as her husband had run paid crews until the service was defunded. Margaret died two years after Capt. Mills.

It was the Harbourmasters job to watch the weather and sea conditions, communicated with ship crews and summon the rescuers. He would fire a signal gun like this one which would be heard across town. The Alexandra lifeboat crew and the Timaru Rocket Brigade would assemble to follow orders. The rest of the town also heard the signal gun and would wander to the cliffs to watch disasters and rescues. The signal gun was on Le Crens Terrace beside the lighthouse. The Harbourmaster and his family lived next door.

Timaru Rocket Brigade pose with their sea rescue apparatus that launched a rope to ships so the passengers could zip line back to shore. Ai llustration based on a photo in the South Canterbury Museum 0840.

ILLUSTRATION OF A ROCKET BRIGADE RESCUE. The British Coastguard and the Board of Trade, refined and standardised the early sea-rescue rocket-apparatus designs. Image is copyright IstockPhoto which WuHoo Timaru purchased.

Imagine standing on Caroline Bay in the 1870s, watching a ship drag anchor in roaring sea swell. There is no breakwater, no tug, no Coastguard. Only a volunteer crew with a rocket apparatus and the hope that their line reaches the mast in time. The Rocket Brigade saved people on ships close to the shore by firing a small rocket from the beach to carry a light line over the wrecked ship. Once the ship’s crew hauled that line aboard and secured it to the mast, the brigade sent out heavier ropes to establish a strong, taut hawser between shore and vessel. They attached a breeches buoy, for people to climb into. They then hauled each person across the surf to land. It was used in Timaru from 1866.

1932 memorial service at the Benvenue Monument. The Alexandra lifeboat is visible in background. Illustration based on South Canterbury Museum photo 1456

An illustration of a large painting of the wreck of 'City of Perth' and 'Ben Venue' at Timaru hung for many years in the Farmers tearooms and now the painting is at the Port Company Offices, Timaru at Marine Parade. The plate below the painting reads: The Wreck of the Ben Venue and City of Perth 14 th May 1882. Presented to The Port of Timaru Ltd. By Arthur Bradley. Last surviving son of Issac Bradley a member of the rescue crafts crew. The painting is now located at Prime Port office.

After her active service ended, the Alexandra continued to be cared for by the Timaru Harbour Board, before being gifted to the Timaru Borough Council in 1932. That year, on the 50th anniversary of Black Sunday, a memorial service was held at Caroline Bay. The Alexandra stood nearby, already recognised as a vessel of remembrance as well as rescue.

The 1862 Alexandra Lifeboat Connects us to our maritime History. This illustration is based on a photo of the Waterside workers for a parage in 1912, South Canterbury Museum 1543.

Anniversary of Black Sunday parade. Illustration based on South Canterbury Museum photo 1543. Three Timaru Harbour Board floats, pictured at the wharf, prepared for the South Canterbury Jubilee Parade, Timaru, January 1909. Includes the Alexandra Lifeboat and crew, a float with a billboard displaying details of imports and exports at Timaru Harbour at the time and 50 years earlier.

In 1997, the Timaru Maritime and Transportation Trust was established to oversee the lifeboat’s conservation and long-term protection. Following the restoration of the historic 1870s Landing Service Building at 2 George Street by the Timaru Civic Trust, the Alexandra was moved there. Her major restoration was completed by 1999, ensuring her survival for future generations.

After a period in storage, the work of care continued behind the scenes, reflecting more than a century of community commitment to preserving the lifeboat and the stories she carries.

In December 2025, the Alexandra returned to Caroline Bay, housed in a new shelter near the water she once faced. Her return marked more than 160 years of community care, service, and remembrance.

The Blackett Lighthouse and the enclosed harbour transformed safety at Timaru. Before they existed, ships anchored offshore in the open Roadstead, exposed to sudden swell, dragging anchors, and poor visibility. The lighthouse provided a constant visual warning, guiding vessels away from dangerous cliffs and reefs, day and night.

The harbour allowed ships to enter protected water, removing the need for hazardous ship-to-shore transfers and open anchorage. Together, they reduced groundings, collisions, and wrecks, and greatly lessened the need for emergency rescues. Where the Alexandra and Rocket Brigade responded to danger, the lighthouse and harbour helped prevent it.

Surf breaks over the new harbour. Based on a William Ferrier photo.

Ai illustration based on an engraving showing the Timaru Breakwater 1888 Picturesque atlas of Australasia The Picturesque Atlas Publishing Co. A heavy south-easterly swell crashes against the Port of Timaru’s southern breakwater, in a photograph taken around 1898. The completion of the artificial harbour in the 1880s provided ships with a safe haven and enabled the port to expand.

Ai illustration based on a painting by William Gibb 1859-1931 Timaru Harbour 1888 Oil on canvas Aigantighe Art Gallery Collection 2002-10

The building of the harbour changed the coastline at Timaru dramatically. Shingle accumulated south of the harbour, and this new land was used for grain and wool stores and oil tanks. North of the harbour, sand piled up under the clay cliffs to form the beach of Caroline Bay.

The breakwater helped to reduce shipwrecks and loss of life.

The Blackett Lighthouse at Timaru was built in 1877–1878. It was part of John Blackett’s nationwide programme of lighthouses, introduced to improve maritime safety after repeated shipwrecks along New Zealand’s coast. Illustration based on South Canterbury Museum photo 202105704

Keepers weren’t just there to tend to the lens only. They also had to maintain other buildings around the light station and keep things running smoothly. Courtesy RG26: ZZ, Standard Apparatus Plans; Vol. 19, Plate 98. Light Keeper’s Implements, 1862.

The construction of the southern breakwater began in 1878 to protect the port from rough seas. Illustration based on Te Papa. PA.000203. James Balfour surveyed the coast and laid the early conceptual harbour groundwork. John Goodall designed harbour plans and set the development in motion for a viable port. The Wrecks Ceased and the Alexandra retired.

Five members of one family were involved in the Black Sunday rescue effort.

Reunited rescuers 50 years later, Isaac Bradley spent more than 50 years on the Timaru waterfront and became the marine superintendent for the Union Steam Ship Co. He and his brothers Philip and Dan (a trained Alexandra coxswain) all took part in the Black Sunday rescues, at times hauling each other from the surf. Their brothers-in-law, George Sunaway (professional boatman) and Carl Vogeler (Timaru Rocket Brigade), also helped that day. In 1932, 50 years later, three surviving rescuers gathered for a photograph at the anniversary, when the old Alexandra lifeboat was put on display at Caroline Bay.

Benvenue Disaster 50th Jubilee in 1932. Three surviving crew members of the lifeboats involved in the Benvenue wreck in 14 May 1932. Depicts the three men as (from left to right) as Isaac James Bradley, Carl George Vogeler, and Philip Bradley. Illustration based on a photo South Canterbury Museum. 14/05/1932 CN 1457. https://timdc.pastperfectonline.com/photo/06F405BF-F04D-4339-A7A7-381944387269

Vogeler, Carl George, 1860-1934. Bradley, Philip, 1853-1936. Bradley, Isaac James, 1860-1936.

The lifeboat was brought back to the bay on the 50th Anniversary of Black Sunday. It was relocated to the Timaru Landing Services Building on George Street to be rennovated and put back on public display.

When the Te Ana Maori Rock Art Center moved in, the Alexandra moved out and went into storage at the Timaru Botanic Gardens for many years.

The boat was looked after by a trust for many years, and then the Timaru Host Lions championed a new home for the Alexandra at Caroline Bay.

While the lifeboat was in storage a new playground was created at Caroline Bay themed around the areas maritime history. A swing and a flying fox was inspired by the Alexandra lifeboat crew and the Timaru rocket brigade. The playground is used by educators to teach students about the history through play. WuHoo Timaru helped to create signage and resources to support this education.

The boat relocated to a store in town and was washed and spruced up in preparation for its return to the bay. Its care has been led by Phil Brownie over 30 years with many volunteers who have lent a hand.

Local photographer and historian Geoff Cloake studied the boat, and helped research and prepare the history of the Alexandra to produce the information boards on the new shelter.

He imagined what it was like for those brave men in 1882 to row to the rescue of scenes like this.

Alexandra is paraded infront of old grain stores - based on photograph by Geoff Cloake 2025.

The region’s favourable climate, easily worked soils, and good transport links encouraged cropping. Large-scale wheat growing began in the 1870s and peaked in the early 1900s. Much of the wheat was grown by contractors who leased land from the estate owners.

South Canterbury’s European farming history began with the runholders who turned sheep onto natural grasslands. The runs were originally leased, but many pastoralists sought to own them. Michael Studholme at Te Waimate, John Acland at Mt Peel, Edward Elworthy at Holme Station and Allan McLean at Waikākahi were among those who acquired very large freehold estates. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, South Canterbury’s large estates were broken up. Some owners sold them off, and others divided them among their families, as it became clear that smaller farms were viable.

Flour milling became an important industry in Timaru and Waimate, and wheat and flour were exported through Timaru’s port. The peak export years were 1911 for wheat and 1913 for flour. Wheat growing declined during the First World War, and by 1924 wheat was being imported to keep the mills operating.

The Alexandra rolled past D.C. Turnbull & Co, a family business that is closely linked to the success of the Port. Richard Turnbull was involved in the first flour export from Timaru to the United Kingdom. His son David C Turnbull established D.C Turnbull and the business has operated for over 130 years. Arthur Turnbull was awarded a bravery medal for Black Sunday. David watched the disaster unfold as a 10 year old on the cliff. David later donated the bell from the Benvenue Ship to the South Canterbury Museum. South Canterbury township of St Andrews was named after Andrew Turnbull, a local manager for the New Zealand and Australian Land Company. He had a reputation for using colourful language, so was ironically nicknamed ‘Saint’.

A piper marched in front of the lifeboat and escorted it onto the Bay. The Lifeboat was walked across the grass by members of the Timaru Host Lions, and pulled by the local Coast Guard to the waiting crowd.

The local coast guard with the old and the new. The vessels have changed but the mission remains the same: Saving life's on the water. Thank you to all of those Volunteers over the many years past and present that make it possible. Thank you for your dedication and offering to support the opening and supplying the tractor and manpower.

The club members of Timaru Host Lions push the lifeboat into its new home.

It was special to acknowledge the lifeboats past and the present heros who rush to the rescue - the local coast guard.

Local coast Guards in Timaru witnessed their origins return to the bay. Our modern day sea rescuers, the coast guard are also volunteers, funded by the fuel tax on maritime vessels and funded by the community.

The community gathered to hear from the club President Russell Cowes and his wife Annie Cowles who both led the project and put in a huge amount of work to fundraise for the lifeboat shelter at Caroline Bay.

Ceremony guests included local artist and community historian Roselyn Fauth who worked with her father Geoff Cloake, to research and design the information panels on the lifeboat shelter. They are the founders of WuHoo Timaru with Roselyn's husband Christopher Fauth.

In her speech Roselyn acknowledged Phil Brownie who had been every month to the shed, turning the wheels and giving it a squirt of water, to make sure that we actually had something to put in the shed. Over 30 years a trio championed a trust to care for the boat which included Phil Brownie, Bill Steans, and the late Arthur Bates. John Cottle had transported the vessel many times over the years in parades along Stafford St. Timaru Maritime and Transportation Trust formed 30 years ago to take care of the boat and was wound down in 2024.

Fauth explained why this was much more than a lifeboat. The Alexandra is a monument that helped connect people to the town’s seafaring past. There’s so many people that have been involved in it, from the rescuers and heroes to the advocates. The lifeboat connects us to 160 years of our maritime past, when our community had to work together to rush to the rescue of others.

Roselyn congratulated and thanked the Host Lions Club acknowledging it was no easy task to fundraise. “They’re just incredible and I’m in awe of what they’ve achieved with their project partners Aoraki Foundation helping them to raise the funds." The $350,000 building project, initiated by the Host Lions Club to mark its 60th anniversary, meant instead of being locked away behind closed doors in a private building, the lifeboat could now be viewed by the public. Russell Cowells gave a big thank you to everyone who donated to the new lifeboat shelter, whether it’s been a few dollars in the bucket that we shook at the market [Matariki Night Market] or a $60,000 donor.

The building is now officially under the ownership of the council. Mayor Nigel Bowen said the work of the Host Lions Club was greatly appreciated. Nigel Bowen said the boat was close to his heart as it had been on display at the Landing Service Building, the same building that houses his own business Speights Ale House.

Member of Parliament the Hon James Meager addresses the crowd.

Today, the Alexandra remains one of the oldest surviving lifeboats of her type in the world, giving Timaru international significance within maritime heritage. She stands here not as an object of nostalgia, but as a witness.

A very similar lifeboat in Norway.

To courage and loss. To women’s work and community resolve.

To innovation, leadership, and care across generations. To a town that chose to act — and to remember.

The success of our harbour is down to many things including our sea rescuing heroes. Illustration based on a photography by Geoff Cloake.

Images have been illustrated with Ai. see wuhootimaru.co.nz for image sources.

Copyright. Roselyn Fauth & Geoff Cloake - WuHoo Timaru. 2025

Procession of floats along the main street of Timaru watched by large crowd of people lining both sides. Quick glimpse of two aircraft flying overhead, perhaps also part of celebrations.

F H DREWITT PRESENTS JUBILEE PROCESSION TIMARU, NZ, 13 JULY, 1928. Horse drawn buggy. Driver and passengers wear period costumes. Men with bowler hats. Procession parades through main street? Timaru. School students, brass band, cars, buses, Timaru's Lifeboat , horse drawn carriages and fire service. ALWAYS READY fire service truck with smoke billowing out from end of ladder on which fireman is sitting above the motor. School boys on parade. Dominion Motors Ltd 1903 and 1928. Various other interesting floats pass by and the crowd closes in on street at end of parade. Crowds lining both sides of street to view parade. L2 planes in sky. People walking down street.

https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/search/F7142/